Indian Ocean basin: a Detailed Map

The ocean is the heart of our planet and its life support system. In fact, its balance and preservation are essential for the survival and thriving of all forms of life, human and otherwise.

Water covers more than two-thirds of the Earth’s surface and contains about 97% of all the water on the planet, which is formally divided into five main ocean basins due to cultural, historical and geographical factors: the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic and Southern Ocean basins. Of course, these actually form one massive body of water, also known as the Global Ocean, that connects the whole planet.

The ocean does not only provide human beings with food, jobs, life and entertainment, it also maintains the planet’s balance, providing oxygen and influencing the global climate. For this reason, it is essential that we understand the complexity of its role in our lives.

In this article, we will explore the Indian Ocean basin, the world’s third largest ocean basin after the Pacific and the Atlantic Ocean basins. We will not only talk about its details, climate and geology, but will also learn about its ecosystems and biodiversity and how essential it is to protect them from the threats they are facing.

If you want to learn all you need to know about the Indian Ocean basin, you are in the right place, just keep reading!

How large is the Indian Ocean?

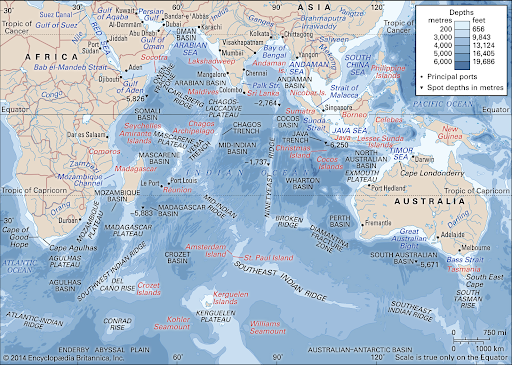

The Indian Ocean basin is located between the Eastern coast of Africa and stretches all the way to the island of Tasmania.

It takes its name from India, of course, and it differs from the Atlantic and Pacific in the fact that, in the Northern Hemisphere, it is landlocked and does not reach Arctic waters, thus lacking a temperate-to-cold zone in this area.

In the West, it meets the Atlantic Ocean at Cape Agulhas, at the southern tip of Africa, and its border runs along the 20° E meridian. In the East the limits of the Indian Ocean are less clear, usually they run from South East Cape, in the southern part of Tasmania, along the 147° E meridian, while in the North the limit is usually set from Cape Londonderry in Australia, crossing the Timor Sea to the southern shores of Java, and then across the Sunda Strait to Sumatra. Another of its boundaries is drawn across the Singapore Strait. In the South, it stretches to the recognized borders of the Southern Ocean basin, which are located at latitude 60° S.

The Indian Ocean basin is the world’s third-largest ocean after the Pacific and Atlantic, covering about 20% of the Earth’s surface. Its area is roughly 5.5 times the size of the USA.

Without its marginal seas, the Indian Ocean basin has an area of about 70,560,000 square km (27,243,000 square mi). The widest point of this body of water is found between Western Australia and the Eastern coast of Africa: it measures almost 10,000km or 6,200 miles.

How deep is the Indian Ocean basin?

The Indian Ocean basin’s average depth is 3,741 metres (12,274 feet). Most of the basins of the Indian Ocean basin are about 5000 m (16404 ft) deep, with some reaching a depth of 6000 m (19685 ft), such as the Wharton Basin. Other parts, of course, have a lower depth, such as the Arabian Sea with its 3000 m (9842 ft), and the Bay of Bengal that only gets to 2000 m (6561 ft) in the south of Sri Lanka.

Its deepest point is found in the Java Trench, also known as Sunda Trench, at 7,450 m (24,442 ft), off the southern coast of the island of Java (Indonesia).

Climate

The Indian Ocean basin can be subdivided into four general climatic regions based on atmospheric circulation: monsoon, trade winds, subtropical and temperate zone, and subantarctic and Antarctic zone.

-

Monsoon zone

The first zone, which extends north from latitude 10° S, has a monsoon climate. This means that during the Northern Hemisphere “summer” (roughly May to October), low pressure over Asia and high pressure over Australia result in strong winds and a wet season in South Asia, the southwest monsoon.

On the other hand, during the northern “winter” (November to April), high pressure over Asia and low pressure in northern Australia bring winds and a wet season for southern Indonesia and northern Australia, the northeast monsoon.

Monsoons are also linked with the El Niño and La Niña phenomena and with the Southern Oscillation pattern of the Pacific Ocean basin. The region is subject to strong tropical cyclones that form over the open ocean and usually occur just before and after the southwest monsoon. The northwestern part of the region has the driest climate, while the equatorial regions are the wettest.

-

Trade-winds zone

The region of trade winds lies between 10° and 30° S. Here, southeasterly trade winds are steady throughout the year and reach their strongest intensity between June and September.

Between December and March, cyclones may occur in the East of Madagascar. Warm ocean currents have a warming effect on air temperature by 2 to 3 °C in the western trade-wind zone over that in its eastern portion. Precipitation decreases from north to south.

-

Subtropical and temperate zone

This region lies in the subtropical and temperate latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, between 30° and 45° S. In the northern part, winds are light and variable, while they become moderate to strong westerly winds in the south. Moving southwards, air temperature decreases. Rainfall is moderate and uniformly distributed.

-

Subantarctic and Antarctic zone

The Subantarctic and Antarctic zone is the coldest and occupies the belt between latitudes 45° S and 60° S. Here we find steady westerly winds all year round, reaching gale force at times. The average winter air temperature varies from 6 / 7 °C in the north to −16 °C near Antarctica. In the summer, temperatures are slightly higher: 10 to −4 °C. Precipitation is frequent and decreases moving towards the south. Even if snow is common in the far south.

Salinity

The salinity of the Indian Ocean basin’s surface waters is between 32 and 37 parts per thousand (ppt) and can display large local differences. High evaporation rates leave the Arabian Sea with a dense, high-salinity top layer.

The surface layer of the Bay of Bengal, on the other hand, is considerably lower in salinity due to the drainage of fresh water from rivers. High surface salinity is also found in the Southern Hemisphere subtropical zone; while low-salinity areas stretch along 10° S from Indonesia to Madagascar.

Temperature

The Indian Ocean basin is the warmest ocean basin on the planet. Temperatures vary according to location and the ocean’s currents. As you can imagine, the nearer we are to the Equator, the warmer the water tends to be. In coastal regions near the Equator, the temperature can reach 28°C (82°F). South of 20° S surface temperatures decrease at a constant rate with increasing latitude, from 22° to 24 °C (72 to 75 °F) down to near freezing at 60° S.

Physiography and Geology

The Indian Ocean basin, compared to the Atlantic and Pacific, is smaller, geologically younger and more complex. It first opened about 140 million years ago, but it was not until 36 million years ago that the Indian Ocean had reached its present configuration.

-

Submarine features

Oceanic ridges are rugged, seismically active mountain chains that form part of the worldwide oceanic ridge system. The ridges are features that show as an inverted Y on the ocean floor. One of the most striking is the aseismic Ninetyeast Ridge, the longest and straightest in the world.

We can also find seamounts, extinct submarine volcanoes, that rise from the bottom of the ocean to heights of at least 1,000 m (3,300 ft). In the Indian Ocean basin, these are especially abundant between Réunion and Seychelles.

Ocean basins are characterised by smooth, flat plains of thick sediment with abyssal hills (i.e., features that are less than 3,300 ft high) at the bottom flanks of the oceanic ridges. The Indian Ocean basin’s complex topography includes many ocean basins, characterised by flat plains and abyssal hills (less than 1000 m high), that range in width from 320 to 9,000 km (200 to 5,600 miles).

In the Indian Ocean basin, the continental shelf has an average width of about 120 km (75 miles) and has the fewest trenches. The Java Trench, its deepest point, is narrow, volcanic and seismically active, and it is one of the longest in the world.

Biodiversity

In the Indian Ocean basin, as the greater part of the water area lies within the tropical and temperate zones, the warmth of the water inhibits the growth of phytoplankton, thus limiting the amount of marine animals it can support.

However, in the tropical zone, we find numerous corals and other organisms capable of building reefs and coral islands that shelter a thriving fauna consisting of sponges, crabs, mollusks, sea urchins, brittle stars, starfish, and small reef fish.

The coasts are usually covered with mangrove thickets, which host a specific animal life. Mangroves are important as they stabilise the land and function as breeding ground and nursery for offshore species.

The Indian Ocean basin is also home to many endangered marine species such as turtles, seals and dugongs (also known as sea cows). Another interesting fact is that, when humpback whales travel from cold to warm water over the winter, more than 7,000 humpback whales migrate to the waters around Madagascar to breed and calve.

Mineral resources

The most valuable mineral resource found in the Indian Ocean is, by far, petroleum. The Persian Gulf is the largest oil-producing region in the world. Both the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal also are believed to have large resources of natural gas and petroleum, and their exploration is still under way, as are the northwestern coast of Australia and the southwestern coast of Madagascar.

Another valuable mineral resource consists in manganese nodules, which are found in abundance in the Indian Ocean basin. Despite advanced technologies, however, the mining process is complex and this has hindered their commercial extraction. Other valuable minerals are ilmenite (a mix of iron and titanium oxide), tin, monazite, zircon, and chromite.

Threats

Deforestation, cultivation, and guano mining carried out by European colonial exploitation had destructive effects on terrestrial ecosystems: by removing vegetation and scraping the land surface, they caused the degradation of much native flora and fauna.

More recently, man-made threats extended to the oceanic environment. The biggest threat is probably pollution, caused by domestic and industrial waste accumulated in coastal waters. This is most evident around India, which is the most populous country of the area.

Another threat is posed by the transport of crude oil across the ocean and sea, which can cause oil spills with disastrous effects on marine ecosystems.

The rise of sea levels, probably caused by climate change, is also a reason of concern as it threatens low-lying coastal areas and islands, such as the Maldives.

References

https://www.britannica.com/place/Indian-Ocean

https://www.indianoceanhistory.org/

https://www.kids-world-travel-guide.com/indian-ocean-facts.html

https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/indian-ocean/

https://eartheclipse.com/geography/indian-ocean.html